As the United States worked tirelessly towards the goal of

putting a man on the moon, there was one area that was a particular

struggle. NASA was used to working with

hardware – big, powerful rocket engines, developing new technology to generate

power, to keep the astronauts alive, and build piping, switching, and electrical

components that had never existed previously.

So they were used to dealing with ‘hard stuff’ like metal, ceramics, and

wire.

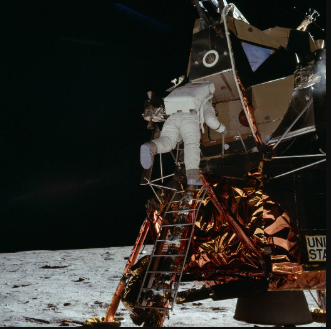

But a big question was going to be how to keep an astronaut

alive on the surface of the moon. At

this point, the suits the astronauts wore were really just a growth of flight

suits, and were really just a secondary protection in case something happened

to the pressurized capsule. A moon suit,

on the other hand, had to literally be like a little self-contained spacecraft

that was worn by the astronaut.

I’ve been to Kennedy Space Center and seen the exhibits of

some of the prototype suits. Some of

them were ‘hard’ suits – made almost entirely out of metal, jointed to allow

the occupant to rotate or move, after a fashion, but obviously extremely

limited in flexibility. There were

rubberized suits as well, but the problem was as soon as they were pressurized,

the internal pressure made it extremely difficult for the astronaut to bend and

move.

So, NASA put it out for bid and asked for contractors to

build a new space suit. Naturally, there

were a number of military and defense contractors who jumped into the fray, but

there was one commercial, consumer manufacturer that ended up getting the

contract.

They specialized in flexible, rubberized or coated garments,

but many people don’t know that the original NASA moon suits were built by a

company named ILC (International Latex Corporation). Most people would know them by their consumer

name, Playtex. Yes, the company that

revolutionized women’s undergarments were taking the lead on building the new

space suit.

However, NASA felt they had to hedge their bets. Playtex was a consumer-oriented enterprise,

and had not been involved in government contracts. So, in addition to Playtex, NASA selected

Hamilton Standard as a partner, with the thought they could better manage the

process. Hamilton Standard was best

known for being one of the primary suppliers of propellers for military aircraft

going back to before WWII.

It was a marriage made in hell. The two companies had completely different cultures

and the clash was almost instantaneous.

They could not come together on how to best progress the project, and

the problems soon became clear to NASA.

Deadline after deadline was missed, or the delivered product was simply

not acceptable. After a few years of

trying, NASA took the drastic step of cancelling the contract.

ILC continued to work on the project, and when NASA later

re-opened the bidding, they were ready with a new proposal. This time, they were selected without the

oversight of Hamilton Standard. However,

they did have to continue working with their former partner, as ILC had the

contract for the suit, and Hamilton Standard received the contract for the

environmental control system (the backpack that contained the systems to keep

the astronaut cool and breathing).

The rest is history.

Playtex used their experience with making flexible clothing and built a

suit that was perfect for the moon. It

has sixteen layers, from a base under-suit with a cooling layer, the pressure

suit, and the final white over-suit made from a new, extremely durable material

called beta cloth. The gloves were made

of a material called Chromel-r, which was a woven metal cloth that cost $50,000

per yard!

I’ve always loved this story. While few of us will ever work on projects the likes of Apollo, we’ve all probably had experiences with conflict on the project team. Sometimes, as shown by the space suit saga, the only resolution is to change the team. People who may have a hard time working together on the same team may work very well together on separate teams with a common goal. There can really only be one leader, in the sense that there should only be one person that can give a ‘go/no go’ answer to resolve conflict and move the project forward.

What lessons do you see in this space suit saga?

For a great documentary series on the development of the

NASA moon suit, check out Moon Machines: The Space Suit.

Like this:

Like Loading...

It’s been 50 years since Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins

pioneered the way to the moon. That

first moon landing was the capping achievement of a nearly decade-long mission,

kicked off by a simple statement in a speech by John F. Kennedy, given to Congress

on May 25, 1961:

“I

believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before

this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to

the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to

mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none

will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

I can’t think of a single project that would compare to this

endeavor today. Those of us who grew up

during this time period can often recall the enormity of what had to happen in

order to accomplish this goal.

Today, we’re surrounded by technology. We take it for granted. I know many people who have severe anxiety if

they can’t connect to others through their various social media channels.

In 1961, Kennedy was starting us off on a journey that required

us to develop technology that didn’t even exist except in the minds of science

fiction writers. Problems had to be

solved that were literally life-or-death for the men selected to pilot the

spacecraft. And all of this had to be

done using less computing power than can be found in a cheap smartphone.

I’m happy to be able to say I was there, in front of my TV

set when Apollo 11 launched. My family

lived in Tampa, Florida, so when the rocket cleared the tower I ran outside and

watched the tiny matchstick flame leave the earth. A few days later, I joined the rest of the

world and watched Neil Armstrong flub his lines when he became the first man to

step onto another world.

Even Neil, Buzz, and Mike were quick to point out that they

did not accomplish this feat on their own.

They always gave lots of credit to the teams back home that developed the

technology, trained them to use it, and supported them on the trip.

I’ve always had a fascination with the space program (if you

couldn’t tell that yet!), so I’m going to spend a few weeks discussing some of

the lessons we might be able to learn and apply by looking at those leaders who

kept to the goal of getting a man from the earth to the moon.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Last time, I started the conversation on building an effective business continuation plan, sometimes also known as a disaster recovery plan. The primary focus then was identifying scenarios, so this time I’d like to go over specifics – what do you need in your plan, setting up the process, and integrating it with your routine.

First, understand that the types of events that can set off

your contingency plan can be wildly varied – from denial of service attacks,

ransomware, to acts of God like hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, or

blizzards. Too often people think only

of natural events rather than human factors.

And the unfortunate fact is the human factor is probably the more

dangerous of them all.

So, here is a brief outline of 8 points highlighting how you should build a contingency plan:

- Build your recovery team. The recovery team should be made up of a

spectrum of talent across the organization, representing the key functions

needed to keep the business running. The

recover team is a key group that is responsible for building and maintaining

the plan. This group should meet

regularly throughout the year to review and keep the plan up to date. At least two key people should be identified

as the plan owners, and a couple more could be tagged to ‘own’ the

documentation. Each member of the

recovery team should have a hard copy of the plan readily available.

- Build your response team. Separate from the recovery team, the response

team is made up of individuals that represent the various functions noted

below. This may include site contacts,

vendor contacts, etc.

- Backups.

Shouldn’t need mentioning, but be sure your backup technology is working

properly. If it’s local, try to build

redundant, geographically separate systems; alternately, go with a cloud-based

solution. This can be a challenge in

large organizations with a large population of mobile users, who store data on

their local device and frequently neglect to back that up to network drives or

initiate the local backup process.

- Identify critical technology. Make a list of the technology your business

uses. Focus on the big application tools

that could have severe impact if they were unavailable. Document each of them separately, collecting

information on where they are housed (local vs. cloud), how they are accessed

(do they need a client? Web-based?), and

who owns the product or vendor relationship.

Document any work-arounds if available; otherwise, document the impact

the loss of the technology will have over time.

- Identify critical sites. If you only have one, obviously that’s the

most critical; however, if your business is multi-site, identify those that are

most critical and how you can shift work if the site is unavailable. Document the impact of the loss over time.

- Identify critical vendors. This is something often overlooked. You should not only create a continuation

plan for your business, but also understand the impact if you lose a critical

vendor. For example, say you use a

shipping company like UPS or Fedex, and sever weather shuts down the

distribution center you use. How do you

work around that, to keep things running? For those vendors that are mission-critical to

the success of the business, it would be a good idea to meet with a representative

and have them share any documentation they have on business continuation.

- Build a communication plan. Your recovery and response teams are obviously

in the loop, but it’s also important that key business leaders are kept

informed of the plan. If the plan has to

be activated, there should also be a communication plan to your employees, so

they know what they should do, or the things they should not. Toll-free numbers providing updates, email

distribution lists, even social media could be used as a means of transmitting important

information to staff.

- Practice, practice, practice! At least once a year, maybe more often,

conduct BCP drills to keep your teams on their toes and identify gaps in your plan.

Create a scenario and act it out; then follow up with test of the communication

plan to your recovery or response teams.

Something that many of these points will have in common is

measuring the impact of an event over time.

What that means is it’s beneficial to have a documented response if an

event lasts and extended period – 1 week, 2 weeks, 30 days, 60 days, etc. Create a checklist of what needs to happen as

time progresses.

For example, if weather prevents a one critical site from

opening, the impact for a week may be minimal and the business can absorb the

loss. If it extends to a 2nd

week, a percentage of the functions handled at that site would need to be moved

elsewhere. At a month, that work may

need to be distributed across several other sites, or fully moved to an

alternate.

Business continuation and disaster recovery can be complex,

but in today’s world it’s a necessary function.

Unforeseen occurrences happen to all of us, and it’s important to be

well prepared. A BCP that has good business representation, is thoroughly

documented, and frequently simulated can prepare you for the unexpected.

Like this:

Like Loading...